The Way Forward For Humanity

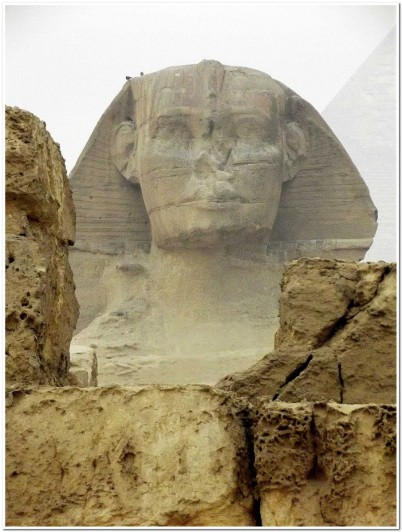

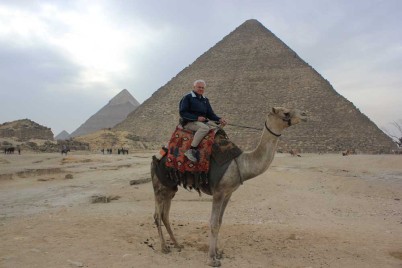

A Lesson on Brotherhood from Ancient Egypt - By Warwick Keys

Warwick Keys looks to Ancient Egypt’s wisdom to find the source of the unifying esoteric beliefs behind a civilisation.

The term ‘brotherhood’ is often tripped off the tongue by Theosophists. ‘Brotherhood’ is easy to talk about but – easy to say and so very hard to put into practice. And yet the practice of brotherhood is central to our beliefs. The First Object of the Theosophical Society is “to form a nucleus of the Universal Brotherhood of humanity without distinction of race, creed, sex, caste or colour.”

The whole concept and birth of the idea of brotherhood in the full sense of the expression in esoteric terms remains elusive. Interpretation of the term is different for each of us. In fact there is often a misunderstanding of the depth of meaning of what brotherhood is about.

I would like to take you on a journey of discovery – a search for the origin and meaning of ‘Universal Brotherhood.’

Ma’at was the cosmic glue that held Ancient Egypt together for millennia. Ma’at as a principle was fashioned to meet the complex needs of the emerging Egyptian state which embraced diverse peoples with conflicting interests. The system was developed to avoid chaos and it became the basis of Egyptian law.

Ma’at represented the ethical and moral principles that every Egyptian citizen was expected to follow throughout their daily lives. The King’s prime duty was to uphold Ma’at. It was believed that if the king steadfastly maintained Ma’at as the guiding principle for Egypt then all would be well for the king, the people, all living creatures, their environment, the heavens above and the whole future of the civilisation.

What was Ma’at?

Ma'at was the ancient Egyptian concept of truth, balance, order, law, morality and justice. Ma’at was personified as a goddess regulating the stars, seasons and the actions of both mortals and the deities, who set the order of the universe from chaos at the moment of creation.

There was an emphasis on Truth. This aspect of Ma’at was paramount. Truth must be upheld at all times. This links with the motto of the Theosophical Society: There is no religion higher than Truth. Helena Blavatsky translated the Sanskrit: Satyat Nasti Paro Dharmah into the motto as we know it.

The term Dharma, however, means much more than religion. Dharma encompasses religion, law, sacred scriptures, doctrine, science, duty, right conduct, virtue, equity, justice and philosophy, all wrapped up together. So the TS motto might better translate as: There is no virtue higher than Truth. This makes better sense. From this it is apparent that Dharma and Ma’at are one and the same, more or less.

All Egyptians were expected to act with honour and truth in matters that involved family, the community, the nation, their environment and God.

Note I said ‘God’ and not ‘gods’. There was only ONE Great Divine Power or Stream recognised by the high priest adepts of Egypt. This Divine Stream was represented physically however by many principles or aspects – hundreds in fact – displayed in the form of the gods and goddesses which populated the pantheon of neterw ;or gods recognised and worshipped by the people.

Written at least 2,000 years before the Ten Commandments of Moses, the 42 Principles of Ma’at ;are one of the world’s oldest sources of moral and spiritual instruction. They form the foundation of natural and social order and unity and include such easily recognisable admonitions as: Thou shalt not kill; Thou shalt not steal; Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour’s goods… etc. These declarations are incorporated in The Book of Coming Forth By Day (the so-called Book of the Dead), in The Teachings of Ptahhotep, and in the writings of other Egyptian sages.

Ptahhotep’s proverbial sayings emphasised humility, faithfulness in performing one’s own duties, and the ability to keep silent when necessary.

The Great Hall

The ancient Egyptians had a deep conviction of an underlying holiness and unity within the universe. Cosmic harmony was achieved by correct public and ritual life. Any disturbance in cosmic harmony could have consequences for the individual as well as the state.

To the Egyptian mind, Ma’at bound all things together in an indestructible unity: the universe, the natural world, the state, and the individual were all seen as parts of the wider order generated by Ma’at.

The significance of Ma’at developed to the point that it embraced all aspects of existence, including the basic equilibrium of the universe, the relationship between constituent parts, the cycle of the seasons, heavenly movements, religious observations and fair dealings, honesty and truthfulness in social interactions.

Interpretations of Ma’at today vary widely, depending on the depth of knowledge and understanding of the researcher.

The majority of Egyptologists have scant knowledge or appreciation of Ma’at , nor do they understand the true nature of any of the gods and goddesses and the principles that they represented. Many have little understanding or appreciation of the underlying esoteric principles involved.

Ma’at is the Divine force or energy that manifests through the sun and flows through the world.

Ma’at is the spirit of beauty and order.

Ma’at also represents truth, justice and harmony when, through human beings, she becomes the conscious exercise of faith in the transcendent creative power embodied in the solar disc.

Ma’at breathes life into everything, the more someone opens their heart to Ma’at the healthier and happier they are as circumstances seem almost magically to favour them.

Hence the famous scene from the (so-called) Book of the Dead (actually entitled The Book of Coming Forth By Day and Opening the Tomb) where a human heart is shown balancing on a scale with the feather the goddess Ma’at always wore in her hair. The Book of the Dead of Ani is full of spells and rules to help Ani travel safely on his journey through the Afterlife. He faces his last and most important test: the weighing of the heart.

The Egyptians thought that a person’s heart showed all their good and bad deeds. Ani’s heart is placed on some scales and weighed by the god Anubis (with the black jackal head) against the feather of truth. If the feather balances with his heart he will survive and continue into the next world. If it is heavier, then he will be eaten by the Devourer, the monster who is part-lion, part-hippopotamus and part-crocodile. Next to the Devourer stands Thoth, the god of Truth (with an ibis head). He checks that the weighing is fair.

The ancient Egyptians recognised that life, health and strength were the reward for what they called ‘Cutting [practising] Ma’at with their every thought, word and action. Immortality could only be achieved through ‘the intelligence of the heart’.

There was nothing abstract about the ancient Egyptian religion. In the Egyptian world each human being was part of the cosmos. As living matter, all have the ability to receive solar energy through the heart, to transform it, and to send it back out… all quite esoteric.

The ancient Egyptians believed that a harmonious flow of solar energy, when transformed into words, involved growth on many levels: inner growth, inner happiness, and outer growth through physical and material prosperity. They also believed that the obstruction of the flow of energy would mean a crisis: destruction, misery and even death.

The ancient Egyptian understood the importance of the proper flow of thought. They also understood how much physical as well as intangible exchanges bring wealth in the tangible as well as in the intangible world.

This all sounds familiar to modern Theosophists.

Finally, it is religion in the Judeo-Christian sense of the term which has resulted in the disappearance of Ma'at as originally understood by the great Egyptian Adepts. This departure can be seen to be regrettable. It could well have major consequences.

Now in the 21st century, a new concept is necessary to maintain social cohesion. The Egyptian concept of Ma’atis being supplanted by the lofty ideal of Universal Brotherhood. All we have to do is accept the full understanding of the concept within our inner being and put it into action – and not just talk about it. All we have to do? It is so easy to talk about and so hard to put into living daily practice.

The call is to live Universal Brotherhood in the Light of the transcendent Ma’at.

Warwick Keys, TSNZ Past National President and current committee member for the Wanganui Branch, is a long-time theosophical student, TSNZ national speaker and meditation teacher with a background of research, writing, business, national politics, history study and photography. Warwick has had a deep, lifelong interest in Egypt.

--- Published in the TheoSophia issue, March 2015